The elements that moved me to write Post Pardon–yes, there are fairies involved!

Originally written for a graduate class, The Irish Female Imagination, taught by Margaret O’Brien at UMass, Amherst, in 2004.

Post Pardon is a series of poems loosely based on the death of prize-winning poet Reetika Vazirani, who killed both herself and son in a murder-suicide. Her two-year-old son’s name was Jehan Komunyakaa, bearing the same last name as his father, the Pulitzer Prize-winning poet Yusef Komunyakaa. Reetika and Jehan were found dead July 18, 2003, in the home she was housesitting, on the dining room floor, parallel to each other, with cuts to the left wrist and a kitchen knife at Reetika’s side.

What sparked my initial interest in this story is that three weeks prior to their death, Reetika, Jehan, Yusef, and myself were at the Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh. Yusef gave a reading, and they came to support him. During that same week, Yusef instructed a workshop I attended. In it, he told us to: “work with the content; to not constantly cut it all out, but save as much of it as possible.” Now, those words are quite chilling. The purpose of Post Pardon is to restore the cut content.

People who knew Reetika and Jehan, who met Yusef, all wondered how something like this could happen. People who had never met any of them but read their work wondered what would drive a person to do that. Everyone who knew this story wondered: why? Post Pardon is an investigation of that why; it is an effort to occupy the mindset of a person who would commit an act of murder-suicide in such a way where reason is not given, judgment is not passed, or excuses are formulated. The series of poems is a chorus of voices speaking from the interiority of a woman who contemplates life: the taking of her own and that of her only child.

In trying to inhabit the emotional and mental space of someone who commits an act of murder and suicide, I had to find a way to articulate it without saying death, killing, murder, suicide, etc. The language best suited to speak this was limited and bogged down with blame, shame, and insensitivity. Furthermore, such words are abstractions. When read or heard, they evoke the clichéd, commonly played upon images and stereotypes.

I needed fresh words and unrealized images to offer a tale unheard. I didn’t want the poems to be an act of shaming Reetika or any other person who has killed themselves or their children because I believe it is the feeling of alienation that is the source of such problems. Secondly, I had to divorce myself from the details of this particular incident. Staying so closely connected to one story impeded my ability to recognize that what Reetika did was not unique. Once I set myself free of her story’s confines, the possibilities of creating a female persona became limitless.

In developing alternative ways of approaching my female subject, I looked to the poetic strategies of Medbh McGuckian and Nuala Ni Dhomhnaill. What attracts me to McGuckian is her ability to imagine and then, therefore, create a world of her own. And often, that world is engendered in the female experience, an emotional landscape that does not seek to limit, truncate, or obfuscate. As a result, McGuckian presents to the reader a language that is formulated on conceits that originate from a woman’s worldview. “Four O’Clock, Summer Street” illustrates some of the elements that I appreciate about McGuckian’s work:

As a child cries, all over, I kept insisting

On robin’s egg blue tiles around the fireplace,

Which gives a room a kind of fly-heartedness.

Only that tiny slice of the house absorbed

My perfume—like a kiss sliding off into

A three sided mirror—like a red brown girl

In cuffless trouser we add to ourselves by looking.

She had the boy-girl body of a flower,

Moving once and for all past the hermetic front door. (102)

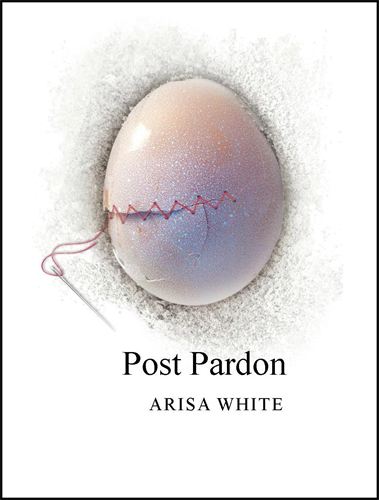

The surreal imagery dissolves borders. The characteristics of one object can be worn by another. Essentially, each body blends and slides and is able to move “past the hermetic front door.” The child’s cries are not in just one home but reach out into the community, into the world. And the color blue of a robin’s egg can become the floor beneath a person’s feet. McGuckian brings to the forefront the beauty and marriage of the boy-girl body of a flower within the structure of a red brown girl. This poem also is an example of McGuckian’s use of color. The employment of blue is pervasive throughout her work, and each time it appears, it is imagined differently. The color is consumed, worn, and embodied; its entry is not barred from anywhere. Her poems string together in color and in Post Pardon, red courses throughout the series. It is a way of leaving hints of what is to come and creating a vocabulary of images. So when the reader reaches the bloodshed, they will be forced to confront that image with the images I have already given them. By devising alternate ways of looking at things, the reader shares the female persona’s perception of reality and, therefore, her existence. This point is addressed as “Four O’Clock, Summer Street” continues:

I knew she was drinking blue and it had dried

In her; she carried it wide awake in herself

Ever after, and its music blew that other look

To bits. If what she hunted for could fit my eyes,

I would shine in the window of her blood like wine,

Or perfume, or till nothing was left of me but listening. (102)

In McGuckian’s work, you are compelled to hunt for the images that will fit into your eyes. Her language is visceral; even though it may elude meaning, she permits you to respond to the mood of her interconnected images. In these lines: “Only that tiny slice of the house absorbed/ my perfume—like a kiss sliding off into/ a three sided mirror….” I react through and with something unbeknownst to me; it is definitely not language as we know it. It is an articulation through the skin of the feeling that happens in the heart and belly. It is true that McGuckian’s poetry is abstract; I believe the reason is that we still remain unclear about what happens to us on a bodily level. This may be the flaw of having our systems of meaning based on a patriarchal point of view; it has worked to exclude how Others make sense of their world. The refreshing aspect of McGuckian is that her language is rooted in the pores, in a metaphor system that starts from the inside out, “offer[ing] alternative social visions that do not conform to existing modes” (Brazeau 128). In Post Pardon, I use this strategy of reinvesting language with new meaning, letting it spring from a female’s subjectivity, from the way she moves in the world, insofar as to allow her to be heard without the damning consequences of a language that will condemn her.

This remains, for me, an important insight, addressed by Helen Blakeman in her essay “Metaphor and Metonymy in Medbh McGuckian’s Poetry”:

[Mc Guckian’s] poems seduce the reader into believing an essential truth will be revealed, and yet the meaning is constantly deferred: sometimes by a careful twist and placed out of reach after the reader thinks it has been grasped. Furthermore…not only is there no unified or stable meaning, but there is also no unified or stable self. (66)

In tackling how to write my poems about Reetika, I kept that statement in mind, treating my subject matter as McGuckian does: slippery and with no structure for hold.

Furthermore, the persona that is modeled after Reetika enters madness; she is not unified or stable. This is when my focus began to shift. The self I was interested in exploring for Post Pardon did not occupy the public arena, where one can easily mask wellness by saying the right things or having acceptable behavior; I was interested in the point of view from an extreme state of mind.

And this is when Nuala Ni Dhomhnaill grabbed my attention. Ni Dhomhnaill writes about transitional spaces between sanity and insanity in relationship to women. Through her poems, she answers the question of what strong women do with all their strength when they go to the extreme. She attempts to get inside the heads of the women who go over the edge, but she writes about it in a matter-of-fact manner. She is able to present things as ‘normal’, because Ni Dhomhnaill uses a language expression that “acknowledge[s] the simultaneous existence [of] the otherworldly and the worldly” which challenges our usual way of understanding things (qtd. in The Irish Female Imagination). In “Battering,” the speaker narrates from an extreme state:

I only just made it home last night with my child

from the fairy fort.

He was crawling with lice and jiggers

and his skin was do red and raw

I’ve spent all day putting hot poultices on his bottom

and salving him with Sudocrem

from stem to stern.

Of the three wet-nurses back in the fort,

two had already suckled him:

had he taken so much as a sip from the third

that’s the last I’d have seen of him.

As it was, they were passing him around

with such recklessness,

One to the next, intoning,

‘Little laddie to me, to you little laddie.

Laddie to me, la did a, to you laddie.’(164)

Ni Dhomhnaill brings the fairy world into the imagination of the speaker. By doing so, she does not need to explain that this woman is in an alternate state of consciousness because such complex ideas are embedded into that otherworld. The speaker’s murderous urges are transposed on the three wet nurses; they serve as the other self who is capable of committing a harmful act against her child. Irish mythology offers Ni Dhomhnaill a whole other landscape and her use of Gaelic. In such spaces, she has the words to speak about madness; she has the ability to speak about dissociation as if it is an act of breathing. So, despite the subject of the poem being off-kilter, she can use the fairy world as a mirror to reflect her deep personal struggle.

I came amongst them all of a sudden

and caught him by his left arm.

Three times I drew him through, the lank of undyed wool

I’d been carrying in my pocket.

When a tall, dark stranger barred my way

at the door of the fort

I told him to get off side fast

or I’d run him through.

The next obstacle was a briar,

both ends of which were planted in the ground:

I cut it with my trusty black-handled knife.

So far, so good.

I’ve made the sign of the cross

with the tongs

and laid them on the cradle.

If they try to sneak anything past

that’s not my own, if they try to pull another fast

one on me, it won’t stand a snowball’s

chance in hell:

I’d have to bury it out in the field.

There’s no way I could take it anywhere next

or near the hospital.

As things stand,

I’ll have more than enough trouble

trying to convince them that it wasn’t me

who gave my little laddie this last battering. (164)

What is so appealing about this poem is that the speaker has gone someplace that is perilous to herself and her child, yet she still has the ability to speak it. Furthermore, I am drawn to hearing what the speaker has to say because the subject’s language and rendering is not clichéd. As a result, my emotional response to the poem is not attached to a societal expectation of how I should react to a woman battering her son. Ni Dhomhnaill’s use of Irish mythology is a way of recovering the female body; it is an act of extending her language to incorporate more than one way of expression.

To apply this idea to Post Pardon, I utilized a system of images and stories based in Caribbean folklore. When trying to decide what I could use to create a system of metaphors, I selected what was readily available to me. Caribbean culture, mainly Guyanese, has presented explanations for the events and occurrences that elude logic and rationale. Rooted in an ethos that allows for the living to talk to the dead, travel through water from one country to the next, and kill her son, the female persona of Post Pardon can enter these realms while maintaining the plausibility of the voice.

Caribbean folklore allowed me to imagine different possibilities for my subject’s state of mind. For instance, it is believed in Haitian culture that when a person dies, their spirit goes to live in a place described as being below water. The female persona of Post Pardon is visited by her father, who too committed suicide, and his arrival is marked by water imagery. His visitation situates her in a position of vulnerability and longing for the company of her father, who was absent throughout her life. Being able to create various possibilities of how she lived and felt in the world humanizes this tragic event, thereby restoring an empathetic relationship between her and the reader.

Another way in which Post Pardon attempts to resuscitate a feeling of interconnectedness between the silenced and heard, the living and dead, and the reader and speaker is by layering voices. My observation of Ni Dhomhnaill and McGuckian’s work is that their stylistic choices about voice bring the female subject to life without being overly narrative or confessional. As a result, the poets do not recreate their own biography but give more attention to the female of their poems. The personality of the female persona can take ownership of language in Ni Dhomhnaill’s poem; they are a “self-possessed, erotically frank, voracious, veracious, independent voice” (qtd. in The Irish Female Imagination). They are capable of telling their stories and remembering their desires: “But when I recall/ your kiss/ I shake, and all/ that lies/ between my hips/ liquefies/ to milk” (“Pog” 129). As well as validating and identifying others: “Whoever you are, you are/ The real thing, the witness/ Who might lend an ear/ To a woman with a story/ Barely escaped with her life/ From the place of battle” (“You Are” 172). In McGuckian’s poems, the female voice refuses stability, inviting in her throat not only the ‘I’ but the second and third person as well. By countering the way in which a story is told, the female subject narrates according to how she makes meaning of the experience:

White on white, I can never be viewed

Against a heavy sky—my gibbous voice

Passes from leaf to leaf, retelling the story

Of its own provocative fractures, till

Their facing coasts might almost fill each other

And they ask me in reply if I’ve

Decided to stop trying to make diamonds. (“Venus and the Rain” 97)

This moment becomes personified, and the poem becomes peopled. There is a feeling of a voice amplified, objects enter communication with the speaker, and the ‘I’ engages the environment as if it is a third person.

Ni Dhomhnaill’s female persona is direct by not letting life mysteries reside in the complexity of language. McGuckian indirectly speaks about an event, a moment, or an experience in such a way that her female subject and the environment co-exist without distinction. Essentially, McGuckian elevates language as the subject of the poem; therefore, all can interact and be imagined. In writing Post Pardon, there are four distinct voices that make up the series. Some of the voices use language as a subject, some incorporate the frankness of Ni Dhomhnaill’s female personas, and they all are interested in telling a story that can make simple and clear this particular life mystery.

Let me introduce you to the voices of Post Pardon: One is that of the female persona, telling the incident in a straightforward, linear fashion. The other is an extension of the female persona, but this voice is spending time at the edge; it perceives the world by first translating it through the body. The third voice is distant and hallucinatory; it beckons the female voice to the unspeakable. The fourth is that of an outside female who is connected to this narrative by way of the spirit world; she is followed by a ghost of a young boy no more than five years old. As a way to differentiate each voice, they are assigned a particular placement on the page. When the poem moves to a different position, the voice changes. I wanted to create in the series a feeling of an echo, a splintering of the self into many, to illustrate that in the head is housed a chorus.